Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Disabling Trifecta of Neuroendocrine Disorder, Autonomic Dysfunction, and Autoimmune Disease

Chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis¹ (ME/CFS) is a neuroendocrine and autoimmune disease with a disabling and systemic impact (Nguyen & Wills, 2019; Wirth & Schienbenbogen, 2021). For clinical diagnosis, an individual must present with fatigue lasting at least 6 months, as well as 4 or more of the following symptoms: joint pain, muscle pain, headaches of a new severity or type, post-exertional malaise (PEM) lasting 24 hours or more, significant impairment in short-term memory and concentration, sore throat, tenderness in lymph nodes, and unrefreshing sleep (Daniels & Salkovskis, 2020; Morris & Maes, 2013; Wirth & Schienbenbogen, 2021). Other reported symptoms include gait disturbance (Barnden et al., 2019), flu-like symptoms (Morris & Maes, 2013), sensitivities to food, light, sound, odors, and temperature (Myhill et al., 2009), muscle weakness, orthostatic intolerance, exercise intolerance, hyperalgesia, and intestinal complaints (Wirth & Schienbenbogen, 2021).

Etiology

Recent research supports a theory that increased sensorimotor white matter in individuals with ME/CFS is associated with compensatory myelin upregulation by the thalamus for impaired nerve signal conduction (i.e., decreased myelin in the brainstem). The reticular activation system (RAS) of the brainstem is well-connected to subcortical targets, the thalamus and hypothalamus. Cortical and physical activity feed back to the excitatory glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons in the RAS to regulate cortical arousal levels, sleep-wakefulness, gait selection, and emotion. However, in individuals with ME/CFS, these connections are impaired. Imaging taken during a Rest and Task fMRI experiment instead revealed enhanced hippocampal connections to the cuneiform nucleus of the midbrain and the medulla, suggesting a compensatory role for impaired RAS connections (Barnden et al., 2019). Other recent research implicates impairment in cerebral blood flow (i.e., cerebral misery perfusion; CMP) as a key mechanism for fatigue, muscle pain and weakness, impaired cognition, and PEM. Approximately one third of individuals with ME/CFS have autoantibodies for beta-2-adrenergic receptors, a crucial vasodilator receptor in the heart, brain, and skeletal muscles. Autoimmunity to this receptor can result in CMP, in turn, leading to systemic fatigue and “depletion” of energy reserves (Wirth & Schienbenbogen, 2021).

Prevalence and demographics. Chronic fatigue syndrome affects approximately 0.2 to 0.5 percent of the worldwide population (Daniels & Salkovskis, 2020). Few studies examine ME/CFS through the experiences of people of color in lower socioeconomic classes or community-based settings. Of these few, research showed that Black and Latino individuals experience more severe sore throat pain, PEM, and unrefreshing sleep. Researchers suggest symptom severity may be, in part, due to the fact that non-white participants experience higher social strain, discrimination, and depression (Jason & Torres, 2022).

Impact on Performance and Engagement in Occupation

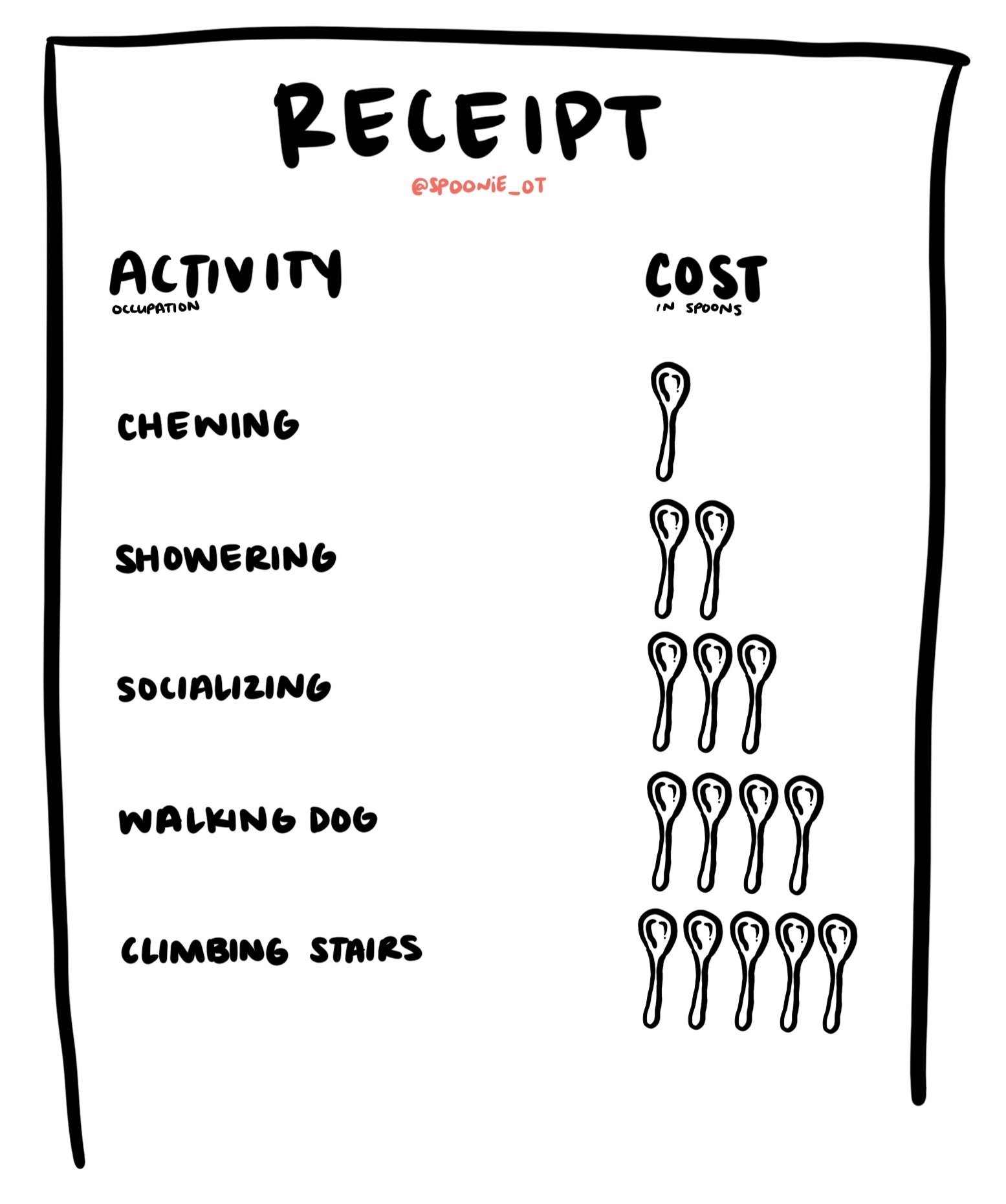

Research repeatedly shows that individuals with lived experience of ME/CFS report having a lower quality of life (QOL) than individuals without ME/CFS (Daniels & Salkovskis, 2020; Harvey et al., 2008; Nguyen & Wills, 2019). One study attributes this decrease to the loss of energy and/or physical or mental capacity to complete voluntary functions (Nguyen & Wills, 2019). Conversely, another study hypothesizes decreased QOL to be maintained through excessive avoidance of activity resulting in deconditioning. However, researchers noted limitations in this theory as participants in their study all reported having highly active lifestyles before the onset of ME/CFS and reported feelings of grief around the change in lifestyle (Harvey et al., 2008). A third study noted the complex cycle of fatigue: engaging in any activity can maintain or exacerbate fatigue, and mutually, fatigue can reduce motivation and compromise one’s ability to function physically or mentally (Daniels & Salkovskis, 2020). In other words, participation in occupation requires planning and effort, both of which require energy. It is this expense of energy–when energy is already scarce–that can decrease intrinsic motivation to engage and participate in occupation.

Interventions, Treatment, and Disease Management

Graded activity treatment is said to encourage patients by increasing activity levels over time to improve exercise tolerance and capacity (Nijs et al., 2011). A 2002 case study of a “highly functional” 52-year-old male with diagnosed ME/CFS reported that graded activity over the course of 1 year supported mildly reduced anxiety and depression. However, a follow-up functional activity assessment (SF-36) showed that the patient was still “considerably more impaired” as compared to the population, suggesting that a return to one’s premorbid state of activity level may prove difficult (Friedberg, 2002). A case study of a 14-year-old girl in Japan exhibiting ME/CFS symptoms was treated with Kampo, an alternative medicine approach. Using combinations of shosaikoto, orengedokuto, and ogikenchuto, the adolescent’s symptoms improved significantly (Numata et al., 2019). It was not specified whether the disease successfully remained in remission at the time of publication. Occupational therapy-specific approaches to working with individuals with ME/CFS are limited, yet focus on the chief complaints of QOL and life satisfaction (i.e., assessments; Bar et al., 2019; Taylor, 2004) and fatigue management (i.e., interventions; Kos et al., 2015). Specifically, using the technique of activity pacing self-management as an intervention to improve the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs). The study concluded that strategic pacing can improve satisfaction with performance of ADLs and support fatigue management (Kos et al., 2015).

Clinical Application

A review of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT) via the AJOT website conducted on May 8, 2024 offered no practice guidelines for ME/CFS. Of 136 articles returned with the search keywords “chronic fatigue syndrome”, 2 articles focused on assessment of QOL and life satisfaction, 1 focused on applying a social model to ME/CFS, and 1 focused on fatigue management. All others were related to other diagnoses with words relating to “chronic”, “fatigue” or “syndrome” or “chronic fatigue syndrome”-like symptoms, but not as a diagnosis. In other research conducted through CLIO, Elsevier, and NIH, current research for ME/CFS focused on graded activity. It is still a testament, both in my opinion and as evidenced in the lack of research available through AJOT, CLIO, Elsevier, and NIH, that occupational therapists can do better as a person-centered profession in the area of chronic conditions such as ME/CFS.

References

Bar, M. A., Bar-Shalita, T., Rosenberg, M. & Rahav, G. (2019, August 1) Participation and life satisfaction among women with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(4_Supplement_1), 7311505115p1. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S1-PO3010

Barnden, L. R., Shan, Z. Y., Staines, D. R., Marshall-Gradisnik, S., Finegan, K., Ireland, T., & Bhuta, S. (2019). Intra brainstem connectivity is impaired in chronic fatigue syndrome. NeuroImage. Clinical, 24, 102045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102045

Daniels, J., Parker, H., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2020). Prevalence and treatment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and co-morbid severe health anxiety. International journal of clinical and health psychology : IJCHP, 20(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.11.003

Friedberg F. (2002). Does graded activity increase activity? A case study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 33(3-4), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7916(02)00038-1

Harvey, S. B., Wadsworth, M., Wessely, S., & Hotopf, M. (2008). Etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: Testing popular hypotheses using a national birth cohort study. Psychosomatic medicine, 70(4), 488–495. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816a8dbc

Jason, L. A., & Torres, C. (2022). Differences in Symptoms among Black and White Patients with ME/CFS. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(22), 6708. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11226708

Kos, D., van Eupen, I., Meirte, J., Van Cauwenbergh, D., Moorkens, G., Meeus, M., & Nijs, J. (2015, September 4). Activity pacing self-management in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 6905290020p1–6905290020p11. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.016287

Morris, G., & Maes, M. (2013). A neuro-immune model of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Metabolic brain disease, 28(4), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-012-9324-8

Myhill, S., Booth, N. E., & McLaren-Howard, J. (2009). Chronic fatigue syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine, 2(1), 1–16. https://www.ijcem.com/IJCEM812001

Nguyen, K., D. & Wills, R. A. (2019, September 18). Chronic fatigue syndrome: An autoimmune disorder of the neuroendocrine system. Journal of Biotech Research & Biochemistry, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.24966/BRB-0019/100004

Nijs, J., Aelbrecht, S., Meeus, M., Ven Oosterwijck, J., Zinzen, E., & Clarys, P. (2011). Tired of being inactive: A systematic literature review of physical activity, physiological exercise capacity and muscle strength in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(17-18), 1493-1500. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.541543

Numata, T., Miura, K., Akaishi, T., Arita, R., Ishizawa, K., Saito, N., Sasaki, H., Kikuchi, A., Takayama, S., Tobita, M., & Ishii, T. (2020). Successful treatment of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome with chronic febricula using the traditional Japanese medicine shosaikoto. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan), 59(2), 297–300. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.3218-19

Taylor, R. (2004, January 1). Quality of life and symptom severity for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: Findings from a randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.58.1.35

Wirth, K.J., & Scheibenbogen, C. (2021). Pathophysiology of skeletal muscle disturbances in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Journal of Translational Medicine, 19(162). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-02833-2

Footnotes

1 Of the studies reviewed, 1 study (Morris & Maes, 2013) classified these myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome as separate and distinct diagnoses.

Published May 10, 2023